What first sparked your interest in the medium?

My first interest in photography began by reading magazines like Reader’s Digest and National Geographic. My father had a cupboard in the hallway, at a young age I would sit on the stairs and read them every night, images in glorious Technicolor of places I had no knowledge of began to dominate my thoughts. I began to understand a particular type of ‘visual language.’

Who were your mentors? Whose work did you admire when you were starting out?

Henri Cartier-Bresson, Gordon Parks, Leonard Freed and Diane Arbus amongst others. There was something about their grainy black and white images, it drew me to their documentary work and still does. That’s why I still shoot on film, usually at 400asa, my 1980s Canon film camera produces the kind of photographs I aim for. An interesting thing about film, each frame is so different, you never know what the outcome will be.

I first came to know your work through seeing pictures you’d taken of the 1985 Handsworth riots. A truly exceptional series. Often professional documentary photography can feel at one remove from its subject. But seeing your Handsworth pictures the viewer feels somehow very closely connected with a ‘social moment’ rather than a photo. opportunity. Can you talk a bit about that work and the way those pictures were made?

The photographs taken during the Handsworth Riots were an important visual record of what I witnessed during the uprising. It was vital in connecting viewers to the moment. By immersing oneself in the midst of things hopefully you can document a number of aspects, not just the sensational and stereotypically photographs that were published by the media. It’s important to remember, throughout the terrible sadness the residents of Handsworth and Lozells had lives to lead. Subsequently a number of the photograph I took can have the look of surrealism. As a photographer, I can only document what interests me. Producing a body of work has its difficulties, when to open and close the shutter.

Of course, you’re also well known for your photographs celebrating black music legends. What particularly stands out from that branch of your practice?

As a child growing up in Birmingham I was inspired by black musicians and also the record sleeves. In later years there were opportunities to spend time and photograph a number of great performers. I wanted to contribute to the musical legacy through my imagery. I recall seeing Curtis Mayfield walking through the Bull Ring or watching Ike and Tina Turner’s riveting performance, The Wailers supporting Johnny Nash at the Top Rank Club. It’s really difficult to say what stands out for me, but probably Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry and Stevie Wonder, spending a few days in their company was eye-opening to say the least! I do hope there is a legacy for the ‘Muzik Kinda Sweet’ and ‘Reggae Kinda Sweet’ photographic archive, those interested in black music may wish to reference the photographs during their research.

From legends to everyday folk: in 2010 you revisited a part of Birmingham that you knew very well as a child to make the photographic essay ‘Sparkbrook Pride’. Once again these have a raw ‘matter of fact’ feel to them and at the same time are deeply intimate, moving portraits of ‘ordinary’ Brum citizens. Can you say what you were aiming for with this project?

With the ‘Sparkbrook Pride’ photographic project, the basic aim was to return to my roots and document the evolving community of new and long-standing residents. It was wonderful to walk the streets and recall long lost memories, better still I was able to photograph a wide range of people from Somalia, Ireland, Pakistan and a host of others. It resulted in a publication with a foreword by Benjamin Zephaniah, we were extremely pleased with the response from the local community and also wider readerships.

As time goes on it seems to me your extensive body of work speaks ever more profoundly about historical, social and political significances. How do you view your photography in terms of not only generating awareness but contributing to societal change?

I have always believed that photography creates awareness and can to a great extent contribute to social change, however it has to be part of the larger conversation relating to the specific subject matter. On a personal note, my photographic practice covers a multitude of strands and travel has allowed me the opportunity to document cultures worldwide. All I can do is to place my work in the public realm, I can’t force the viewer to understand my reasoning for making art.

Last year with Handsworth Revisited you seemed pleased to see your collaboration with Benjamin Zephaniah being posted on the streets of the city. And now you’ve collaborated on this current YSOM project you have work displayed in the public realm again… Can you talk about the pictures you’ve chosen to show via this platform and thoughts you have on sharing your work this way?

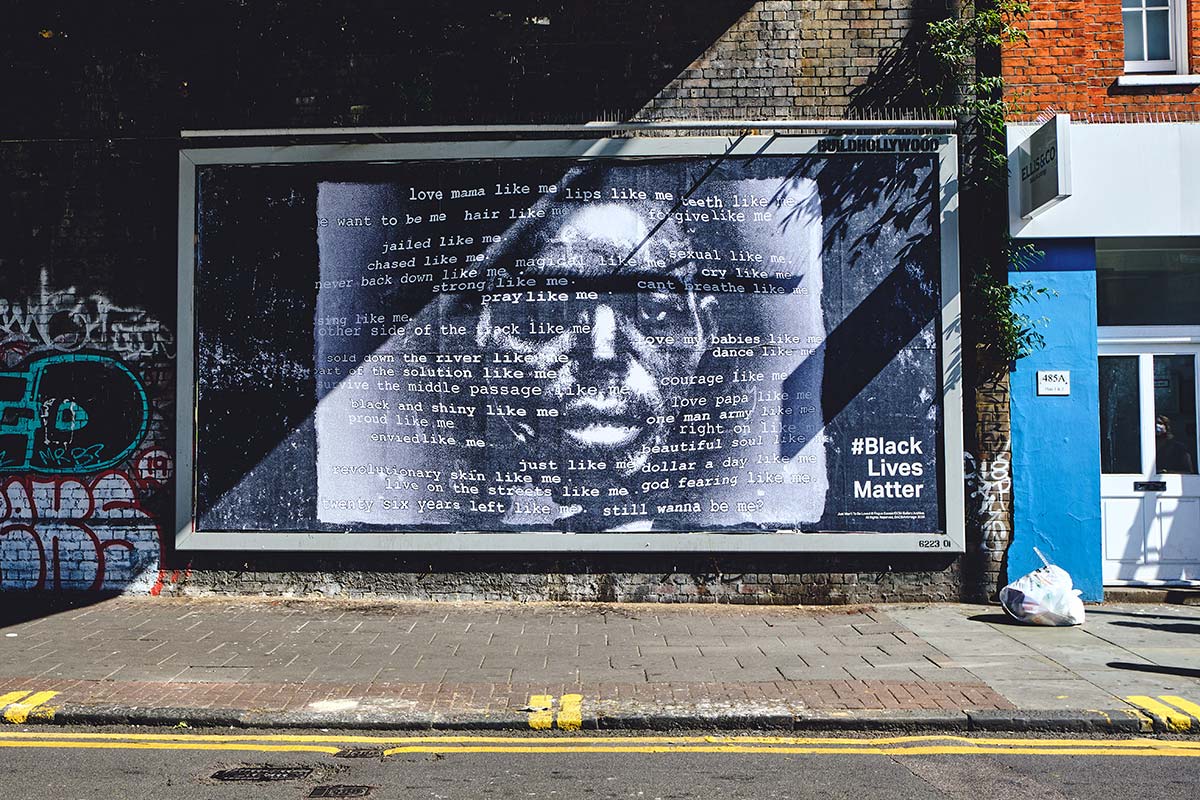

The appeal of having artwork displayed throughout British cities is a simple one, the public have more access to the imagery. Also working with agencies who have an understanding of my work adds more potency and impact towards spreading the particular message I wish to convey. I really enjoy collaborating with teams of inspiring and creative people, they have a way of achieving the best possible outcome. The photographs chosen for the 2020 BLM campaign are straight and to the point, no apologies. ‘Black Skin, White Palm, Same Blood and ‘Just Wan’t To Be Loved’ adds an alternative narrative to the plight of Black people, not just in America but worldwide. Watching a man’s life ebb away for nearly 9 minutes was one of the worst things I have ever witnessed.

Finally, in the light of recent events – the U.S. cop killing George Floyd and subsequent global condemnation and demo.s – do you think it will meaningfully advance the situation for Black, Asian and minority ethnic people? And more specifically will things improve for photographers and other artists who up ‘til now in the UK and elsewhere have been subject to what’s sometimes termed a ‘cultural apartheid’, a systemic racism in the arts that’s hampered the careers of many…

Advancement can only become a reality when there is an admittance that the system is broken, for some, that is a very large and bitter pill to swallow. Careers are hampered by a multitude of factors, we have always been aware of ‘cultural apartheid’ in some cases it can be very difficult to prove but exists in the minds of many. Artists will always find a way to progress. In recent years, the institutions who have unfolded their arms and embraced our culture have found a great weight lifted from their shoulders.

The Wrong Man, London, UK 2001 From the series Schwarz Flaneur © Pogus Caesar/OOM Gallery Archive. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2020

The Wrong Man, London, UK 2001 From the series Schwarz Flaneur © Pogus Caesar/OOM Gallery Archive. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2020

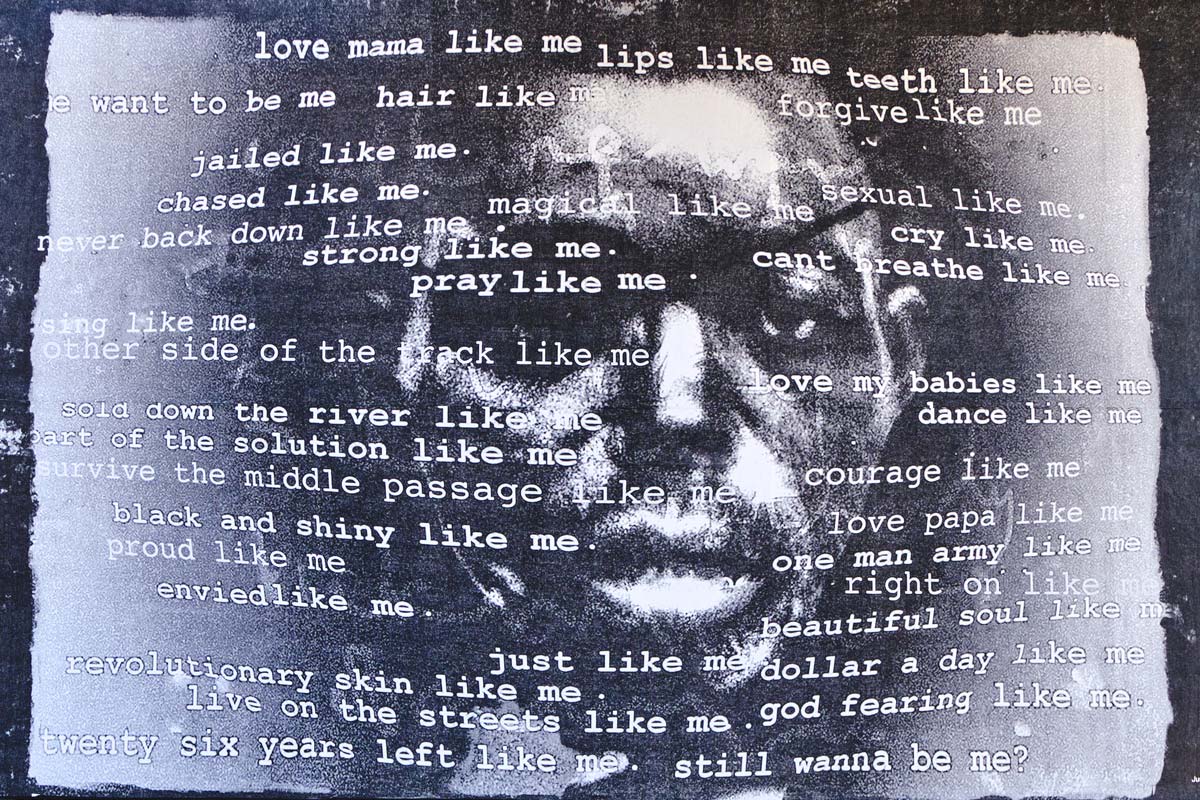

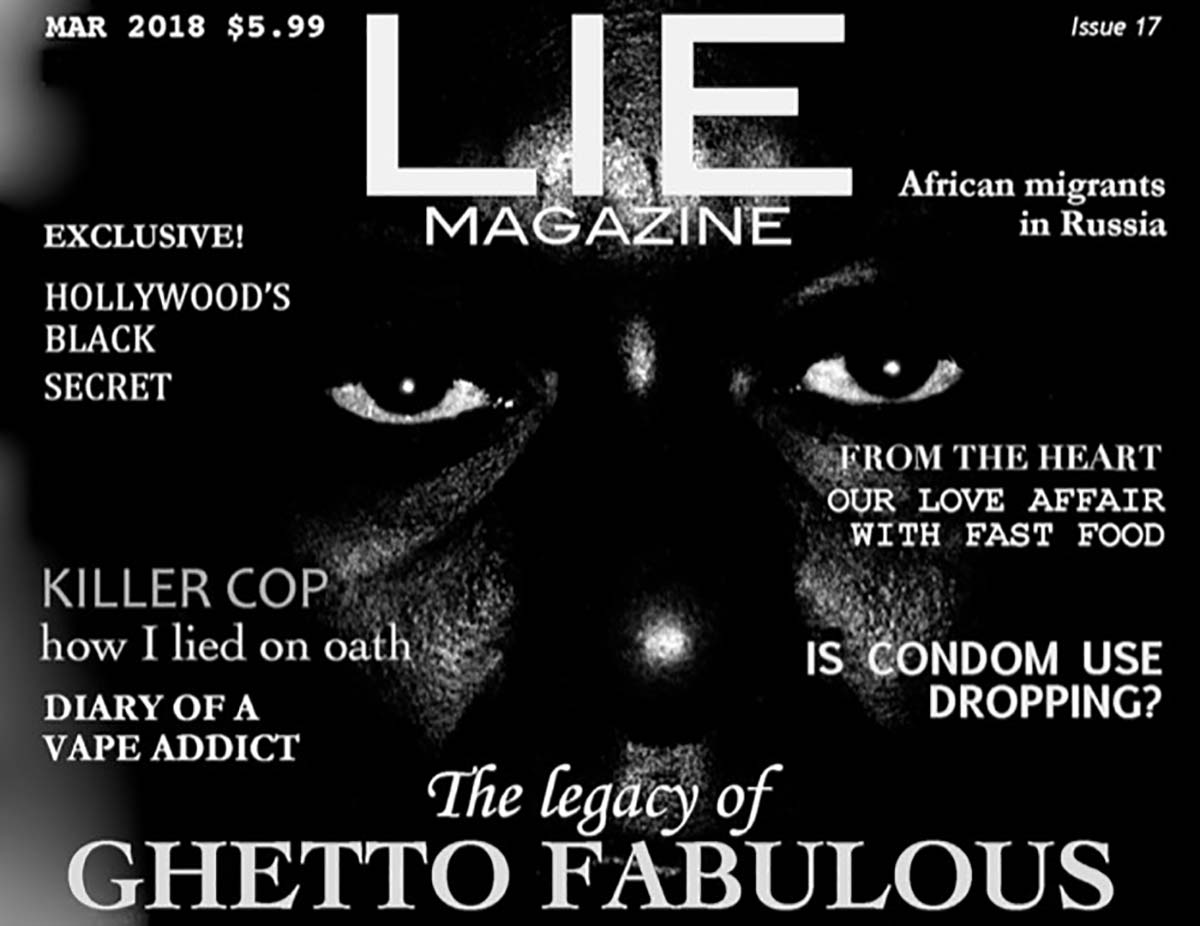

Lie, 2017 From the series Get Naked © Pogus Caesar/OOM Gallery Archive. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2020

Lie, 2017 From the series Get Naked © Pogus Caesar/OOM Gallery Archive. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2020

Handsworth Riots, Birmingham, UK 1985 © Pogus Caesar/OOM Gallery Archive. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2020

Handsworth Riots, Birmingham, UK 1985 © Pogus Caesar/OOM Gallery Archive. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2020

Set The Dogs On Em, 2015 From the series US of A © Pogus Caesar/OOM Gallery Archive. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2020

Set The Dogs On Em, 2015 From the series US of A © Pogus Caesar/OOM Gallery Archive. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2020

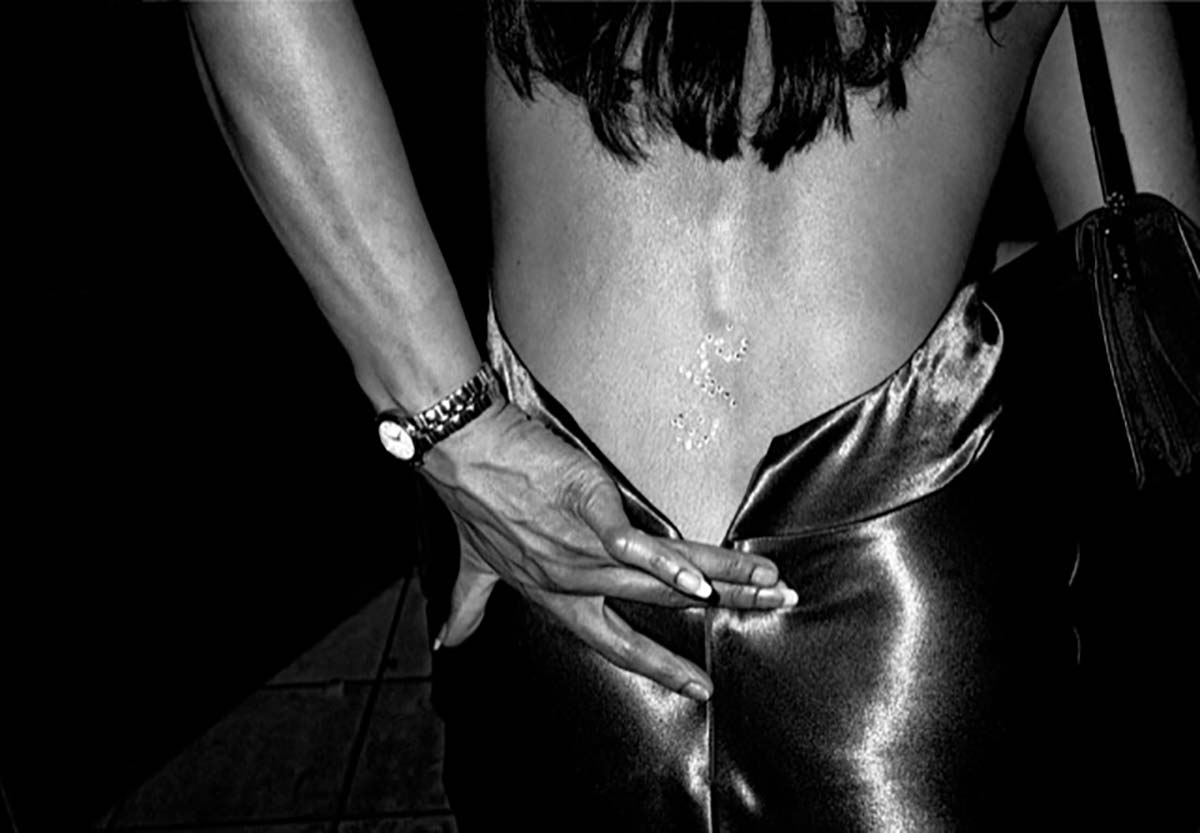

Silver & Skin, Birmingham, UK 2001 From the series Schwarz Flaneur © Pogus Caesar/OOM Gallery Archive. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2020

Silver & Skin, Birmingham, UK 2001 From the series Schwarz Flaneur © Pogus Caesar/OOM Gallery Archive. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2020

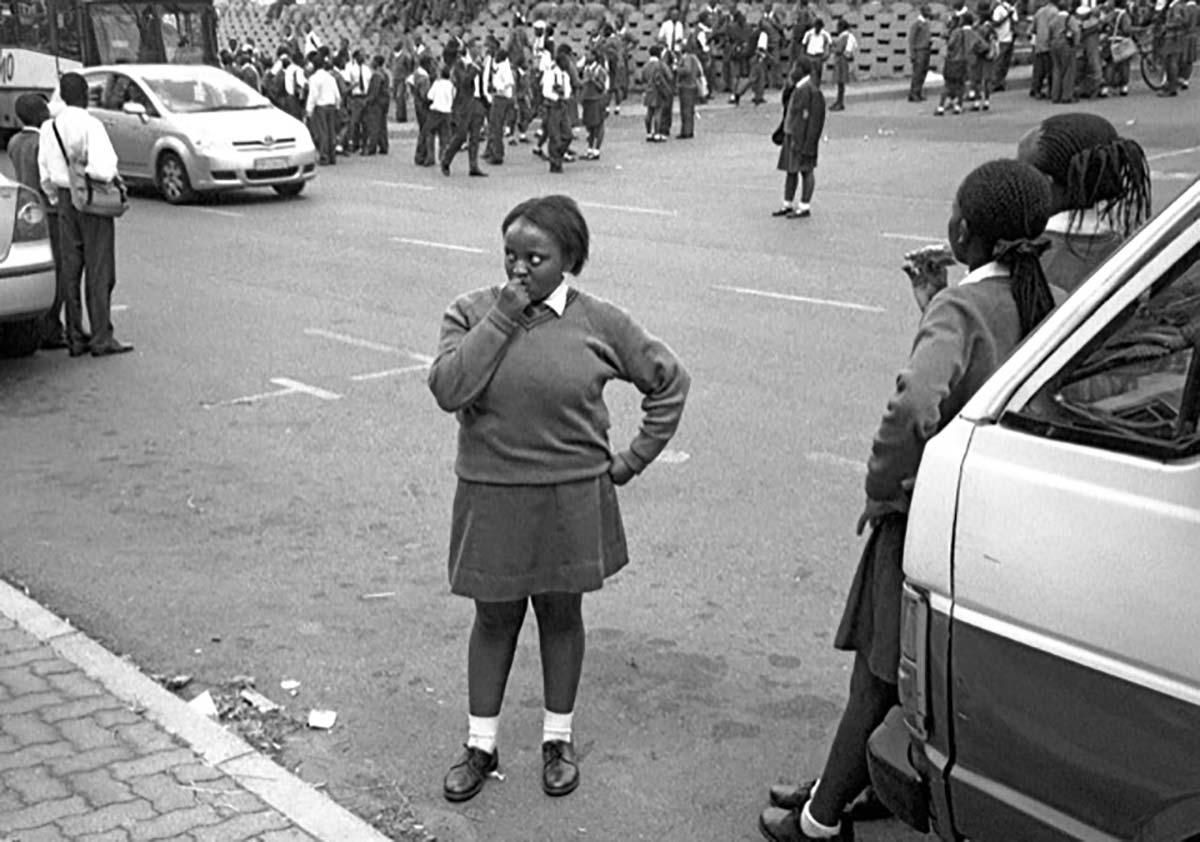

Within Seconds, Newtown, Johannesburg , South Africa 2007 From the series Schwarz Flaneur © Pogus Caesar/OOM Gallery Archive. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2020

Within Seconds, Newtown, Johannesburg , South Africa 2007 From the series Schwarz Flaneur © Pogus Caesar/OOM Gallery Archive. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2020

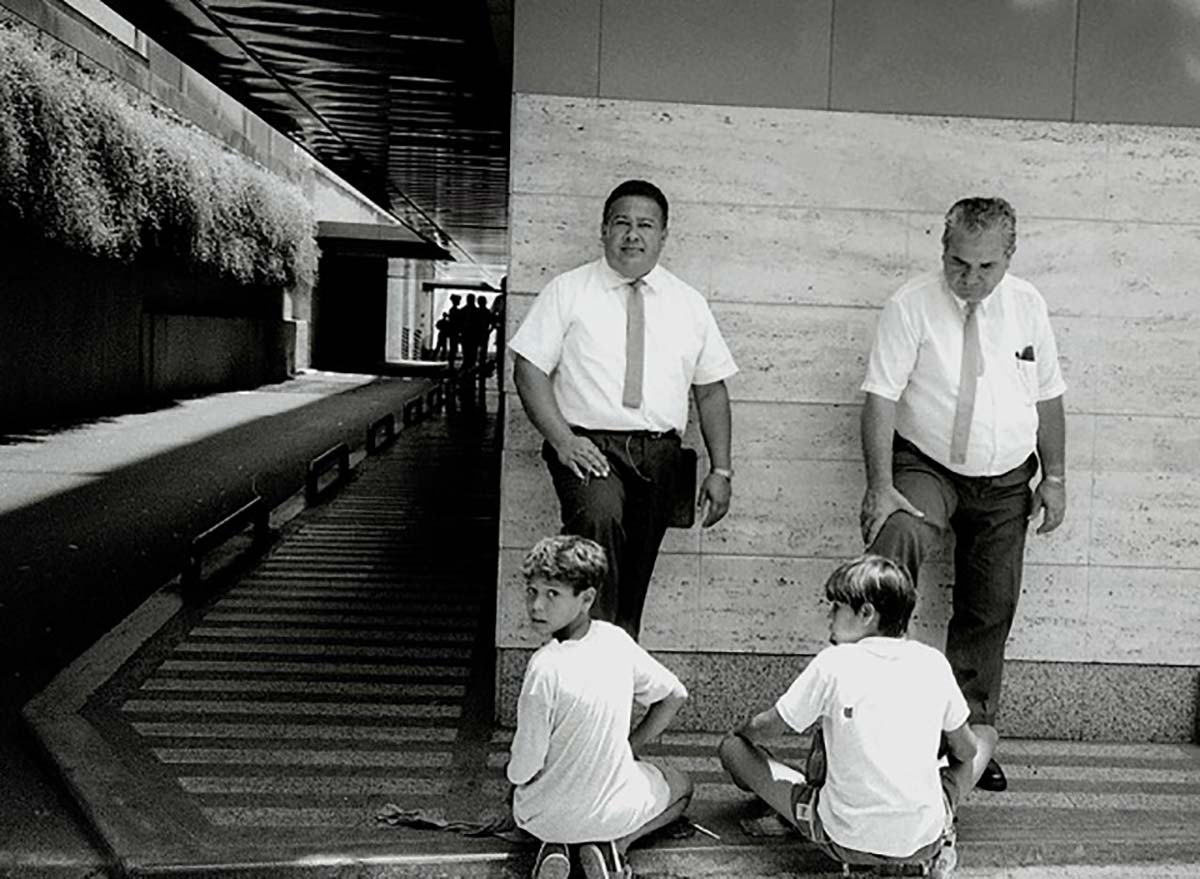

Shoe Shine, Caracas, Venezuela 1991 From the series Schwarz Flaneur © Pogus Caesar/OOM Gallery Archive. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2020

Shoe Shine, Caracas, Venezuela 1991 From the series Schwarz Flaneur © Pogus Caesar/OOM Gallery Archive. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2020

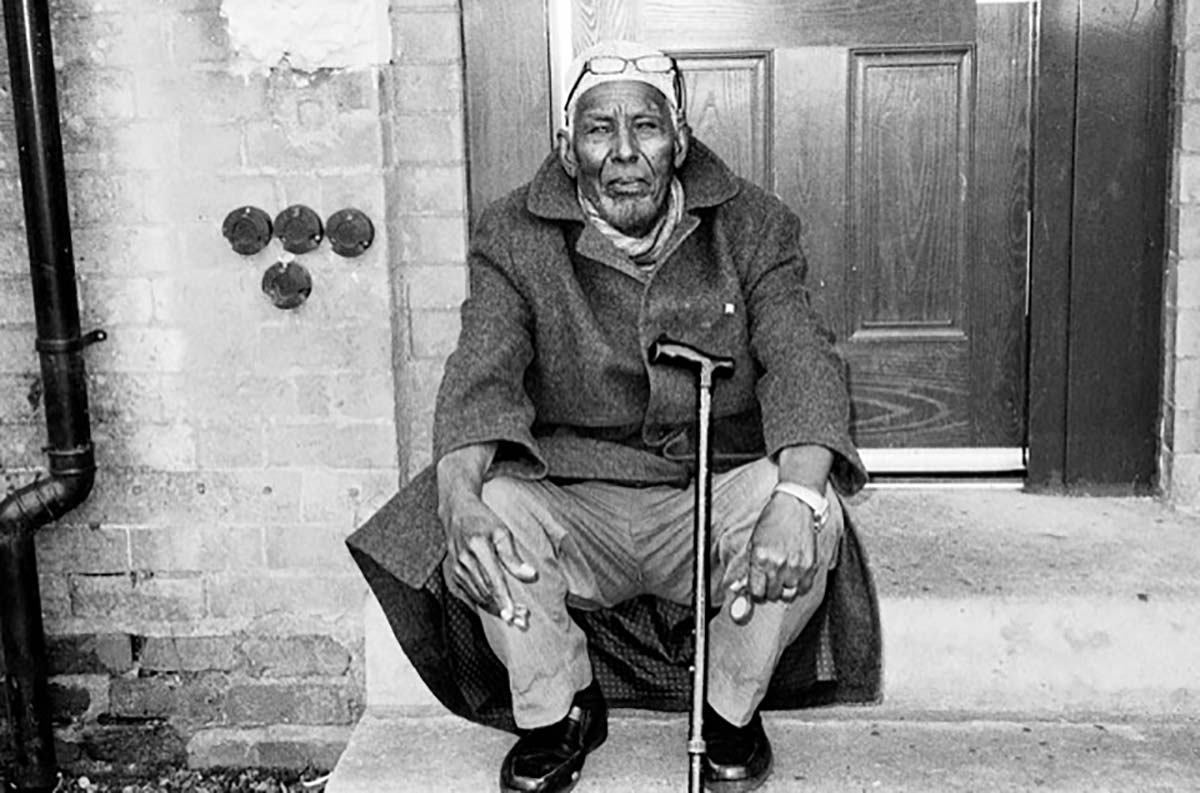

Somalian, Birmingham, UK 2010 From the series Sparkbrook Pride

Somalian, Birmingham, UK 2010 From the series Sparkbrook Pride

Lionel Richie, Birmingham 2004 © Pogus Caesar/OOM Gallery Archive. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2020

Lionel Richie, Birmingham 2004 © Pogus Caesar/OOM Gallery Archive. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2020

Day Trip to the Black Country, Walsall, UK 1986 From the series Schwarz Flaneur © Pogus Caesar/OOM Gallery Archive. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2020

Day Trip to the Black Country, Walsall, UK 1986 From the series Schwarz Flaneur © Pogus Caesar/OOM Gallery Archive. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2020

Protein II, West Bromwich, UK, 1990 From the series Schwarz Flaneur © Pogus Caesar/OOM Gallery Archive. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2020

Protein II, West Bromwich, UK, 1990 From the series Schwarz Flaneur © Pogus Caesar/OOM Gallery Archive. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2020